Andreas Mühe inszeniert. Themen wie Macht, Ideologie, Vergangenheit und Eitelkeit durchziehen die Arbeiten des jungen Künstlers. Als Magazinfotograf ist Mühe durch seine eigenwillige Art Modelle zu positionieren bereits bekannt. Virtuos in Pose gesetzt werden sie zu einem Teil der Inszenierung, zu einem Teil des Bildgefüges. Gerhard Richter läuft auf und ab vor seinem eigenem Gemälde, Paul Maenz posiert neben porzellanweißen Aktskulpturen und Friede Springer dreht sich weg und schaut mit ihren Gästen andächtig durchs Fenster. Die Pose des Abwendens ist eine, die sich im Oeuvre des Künstlers wiederholt. Einen Schwerpunkt der Ausstellung bildet der Bildzyklus Obersalzberg, mit dem sich der Künstler seit 2010 beschäftigt.

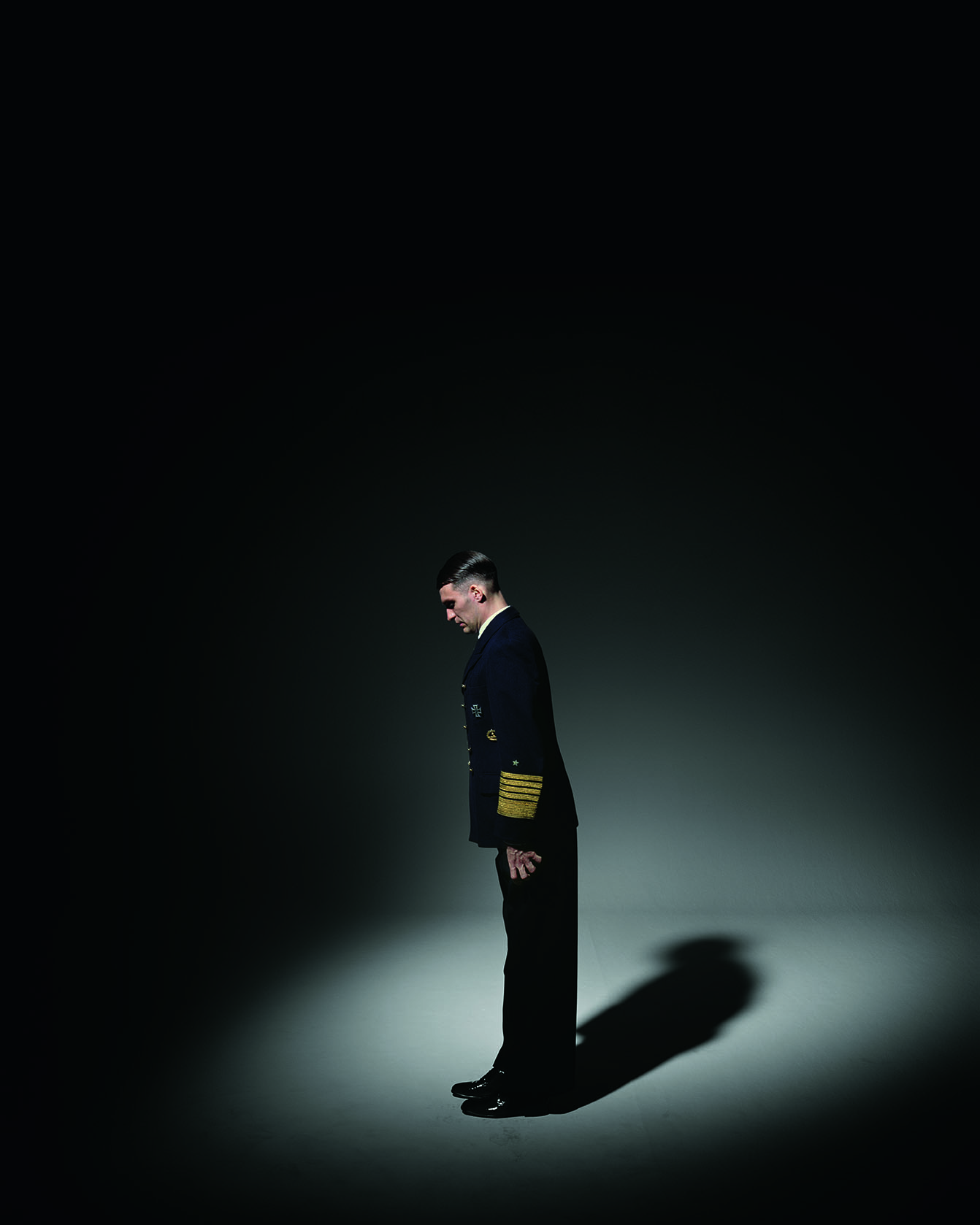

Die in den Landschaftsbildern noch anonym bleibenden Nazis stehen in den Haltungsstudien frontal beleuchtet, in Uniform gekleidet oder nackt im Studio. Die extrem angespannt wirkenden Haltungen orientieren sich an Originalfotos der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Titel, wie „Darges I 44“, oder „Dönitz 43“ verweisen unmissverständlich auf den Referenten, gleichzeitig überspitzen sie in ihrer Unmöglichkeit der Benennung die Inszenierung. Die Zahl gibt Aufschluss über das Jahr, in der das Originalfoto aufgenommen wurde. In fast dokumentarischer Weise entschlüsselt Mühe Dokumente der Zeit und übersetzt sie in seine eigene künstlerische Sprache. Dem Mann in Uniform steht derselbe in einem anderen Bild nackt gegenüber, akribisch in die gleiche Pose gesetzt. Bereits aus der Modefotografie der 80er bekannt ist die Gegenüberstellung von Angezogen und Nackt und wird hier neu interpretiert. Die Anspannung der Muskeln und die Konzentration auf die perfekte Haltung wird erst durch das Fehlen der Kleidung sichtbar. Das Studio ist Raum und Hintergrund zugleich. Dunkel, düster und mit einem verzerrten Schlagschatten erinnert es an die Vergangenheit. Wie Skulpturen, unberührbar, unbeweglich und nahezu dem Lebendigen entzogen, wirken die Männer fast verloren im künstlichen Licht des Studios. Die Darstellung der Macht entlarvt sich als Inszenierung. Aller Aggressivität ihres Status beraubt und dem Geschehen zeitlich entrückt, drücken die Nazis auf Mühes Bildern von vornherein ein Scheitern aus.

Analytisch rekonstruiert der Künstler Aufnahmen deutscher Vergangenheit, die schon vor langer Zeit aus dem Bildgedächtnis verbannt wurden. Seine Referenzperson ist Walter Frentz, ein Fotograf, der das öffentliche Bild des Naziregimes wesentlich geprägt hat. In einer Reihe von Porträts lässt er seine Freunde, dessen Namen als Titelgeber fungieren, in die Rolle des Naziverbrechers schlüpfen. Während Walter Frentz kaum Zeit hatte, seine Modelle in Pose zu setzen, lenkt Mühe alles Augenmerk auf die Stilisierung seiner Protagonisten. Perfektionistisch, in makelloser Uniform, exakt sitzenden Seitenscheitel, vor gleichem rötlichen Vorhang, zeigen „Klemens“, „Patrik“ und „Arne“ ihre Gesichter. Dichte Wälder und hohe Berge, unbezwingbar und archaisch nehmen nahezu die gesamte Bildfläche in den Landschaftsarbeiten ein. Die Verbindung der romantisch anmutenden, fast ins Kitschige übergreifenden, Landschaft mit einem

Offizier oder SS-Mann des Naziregimes wirkt verstörend. Die Wahl des Ortes ist historisch begründet. Die Berchtesgardener Landschaft rund um den Obersalzberg diente Hitler und seiner engeren Gefolgschaft als privater Rückzugsort. Die Menschen sind verschwindend klein in der Landschaft, die Gesichter abgewandt oder nicht erkennbar. Anders als in der deutschen Romantik wir die Besinnung und Reflektion alleine auf die Person übertragen. Die Figuren sind immer exakt in der Bildmitte positioniert, die Natur wird zum bloßen Hintergrund und die

Inszenierung reines Spektakel. Die Mystik der Berge inszeniert Mühe mit mehrstündigen Langzeitbelichtungen. Die Geister der Geschichte scheinen ihre letzte Spur im surrealen Mondlicht zu hinterlassen. Übrig bleibt eine traumatisierte Landschaft, die ihre Vergangenheit wohl nie gänzlich abstreifen wird.

Andreas Mühe stages images. The young artist’s work is permeated by themes such as power, ideology, the past and vanity. Due to his own unique way of staging models, Mühe has already gained fame as an magazine photographer. Expertly positioned in their respective poses, they come to form as a part of the staged image, a part of the pictorial whole. Gerhard Richter walks up and down in front of his own paintings, Paul Maenz poses alongside nude sculptures in porcelain white, and Friede Springer turns away and together with her guests looks reverently out of the window. This pose – the subject turning away from the camera – is one that is repeated throughout the artist’s oeuvre. This exhibition focuses in particular on the Obersalzberg series, which the artist has been working on since 2010. While they remain anonymous in the landscape images, in the pose studies the Nazis stand front-lit, dressed in uniform or naked. The poses, which seem to be full of tension, take their cue from original photographs from the Nazi period. Titles such as “Darges I 44” or “Dönitz 43” make unmistakable reference to the setting, while – impossible to define – exaggerating the staging. The number provides an indication of the year, in which the original photo was taken. In a near documentary fashion, Mühe deciphers contemporaneous documents and translates them into his own artistic vernacular. The man in uniform is faced with the same man standing naked in another image, meticulously positioned in the same pose. This juxtaposition of the dressed and the nude is already a familiar motif from fashion photography of the 1980s, a motif that Mühe subjects to reinterpretation here. The contraction of the muscles and this clear concentration on maintaining the perfect posture only becomes evident when the subject is disrobed. The studio constitutes both the space and backdrop at the same time. Dark, dismal and with a distorted cast shadow, it is reminiscent of the past. Like sculptures, untouchable, unmoving and close to completely removed from the world of the living, shrouded in the studio’s artificial light the men appear almost lost. The representation of power is debunked and shown to be mere staging. Robbed of any drop of aggressiveness denoted by their status and temporally disconnected from past events, in Mühe’s pictures the Nazis constitute an expression of failure from the outset. The artist analytically reconstructs images of German history that had long since been banished from visual memory. His reference figure is Walter Frentz, a photographer who essentially shaped the public image of the Nazi regime. In a series of photographs he has his friends, whose names also function as the images’ titles, slip in to the role of the Nazi criminal. While Walter Frentz barely had time to position his models, Mühe draws all attention to the stylization of his protagonists. Oozing perfectionism, immaculate in uniform, wearing meticulously combed side partings, standing before the same red curtain, “Klemens”, “Patrik” and “Arne” show their faces. Dense forests and high mountains, not to be conquered and ancient they occupy almost the entire pictorial space in Mühe’s landscape works. This combination of the landscapes - romantic, bordering on kitsch – with an officer or Nazi SS guardsman proves quite unsettling. Indeed the choice of location is grounded in history. Hitler and his close followers once used the Berchtesgarden landscape that surrounds the Obersalzberg as their private retreat. Against the landscape the people look minute, their faces turned away or unrecognizable. In contrast to German Romanticism, contemplation and reflection is transferred to the person alone. The figures are always positioned precisely at the center of the image; nature becomes nothing more than a backdrop and the staging pure spectacle. Mühe stages the mysticism of the mountains with long exposure periods that span several hours. These specters of the past seem to leave their last traces in the surreal moonlight. What is left behind is a traumatized landscape which is not quite able to completely cast off its past. Mühe captures his images using an analog large-format camera. The acute focus and brilliance, and something mystical is to be felt in it, is surely down to the choice of technology, if only in part. The size of the photographs – 4 x 5 inches – corresponds to the original format of the negatives used by his camera. Many of Mühe’s works are presented in series whereby their repetition reveals the uniformity of the content. A series of 20 small-format photographs, “Wandlitz” presents the homes of the once most powerful men in former East Germany. Uniform, transformed into the size of a doll’s house bereft of any character, in the images the houses have something rather surreal about them. Mühe only shows female protagonists with their backs turned to the camera. The elaborately braided hair-dos were the true symbol of women in the Third Reich, who stood in the shadow of their husbands and fulfilled the traditional role of the woman. The tattoos correspond to the reality of independent women today and appear rather out of place juxtaposed to the braids. The jet-black background renders the body sculptural, almost haptic in its appearance and is evocative of portrait paintings by the Old Masters. And it is precisely because one is unable to deny Andreas Mühe’s pictures of their aesthetic that they are so unsettling.